DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Artistic co-creation as a decentralized method of peer empowerment in today’s multitude

Marc Garrett

Introduction.

Furtherfield originally created the term DIWO in 2006, to represent and reflect its own involvement in a series of grass root explorations. These critical engagements shift curatorial and thematic power away from top-down initiations into co-produced, networked artistic activities; it is now an international movement and it has grown into something much larger than we imagined.

The practice of DIWO allows space for an openness where a rich mixing of components from different sources crossover and build a hybrid experience. It challenges and renegotiates the power roles between artists and curators. It brings all actors to the fore, artists become co-curators alongside the curators, and the curators themselves can also be co-creators. The ‘source’ materials are open to all; to remix, re-edit and redistribute, either within a particular DIWO event or project, or elsewhere. The process is as important as the outcome, forming relationally aware peer enactments. It is a living art, exploiting contemporary forms of digital and physical networks as a mode of open praxis, as in the Greek word for doing, and as in, doing it with others.

This study investigates why these critically engaged activities were (and are) thought of as essential nourishment not only for ‘individual’ artists, but also as an effective form of artistic collaboration with others, and to a wider culture. It explores the differences between ‘collaborative’ trends initiated by established art (mainstream art) and design institutions, the creative industries, corporations, and independent projects. It examines the grey areas of creative (idea) control, the nuances of power exchange and what this means for independent thinking artists and collectives working within collaborative contexts, socially, culturally and ethically. It also asks, whether new forms of DIWO can act as an inclusive commons. Whereby it consists of methods and values relating to ethical and ecological processes, as part of its artistic co-creation; whilst maintaining its original intentions as a decentralized method of peer empowerment in today’s multitude?

DIWO and New Media Art Culture.

“…the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.” [1] (Catlow 2010)

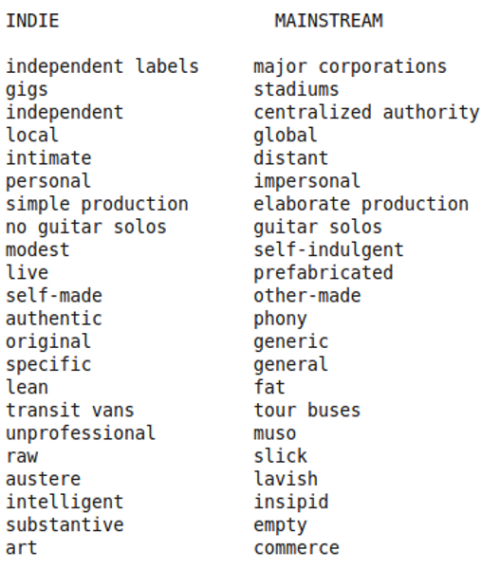

In music and art culture, artists have been defining their autonomy against the dominance of mainstream culture for years. Furtherfield’s and DIWO’S own history began with experimental sound and music, with pirate radio stations and collaborative street art projects in the late 80s and early 90s. A Present-day example where we can see artists carving out their own mutual spaces of independence, is in the contemporary Indie Music scene. In her study ‘Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture)’, Dr. Wendy Fonarow [2] investigated the UK’s ‘indie’ music scene and its culture from the early 1990s to present day. Below, Fonarow presents the different values between mainstream music and the independent music scene.

On the left-side on the diagram there are similar themes and values DIWO also draws upon, as part of its grounded ideas and relational connections with others. DIWO as a practice is different than the Indie Music scene, yet its core values also involve self-governence. The Indie music scene views itself as oppositional to the mainstream music world, viewing it as “corpulent, unoriginal, impersonal, and unspecialized” [3]. Out of these shared values, vital signifiers are formed demonstrating peer empowerment. Like the tribal and anti-establishment elements of Punk, it is a deliberate side-step away from what is seen as the trappings of commercial culture, and its limitations on creative expression. The continuing growth and interest in independent music as it manages to survive seperately from the mainstream, is evident. We only have to view recent revenue making web sites such as emusic, with its international audiences buying Indie music and experimental sounds on-line; a good example of a grass root, networked economy based around social differences in contrast to mainstream dominance. The large site consists of an abundant amount of independent artists selling their work as well as independent record labels.

Even though the values presented by Fonarow also exist in DIWO. In essence, DIWO relates to a varied set of practices still finding its place in the world. This overall field is Media Art, an umbrella term for various ‘art and technologically’ related practices. Born out of art and electricity, it connects to common people through the Internet and as yet, not officially prescribed as a valid form of artistic expression by the art establishment (mainstream art world). Media Art’s historical canons and critical dialogue; no matter how artful, highly skilled, informative, extravagant, original and critical; have been manipulated out of the ‘official’ picture. For years, Media art practice has found itself in the wilderness as wandering nomads, upstarts and outsiders. And even though much of the art work and its consistant and thriving dialogue is ‘up to date’ and contemporary; it is at odds with the mainstream world’s prescribed script of what the dominating art market expects ‘art’ to be. Norman Klein, in his essay “Inside the Stomach of the dragon: The victory of the Entertainment Economy,” writes “We all essentially live in the stomach of the ‘entertainment’ dragon. As a result, it would be near impossible to generate an avant-garde strategy in a world that feels increasingly like an outdoor shopping mall, what I call a scripted space.” [4] (Klein 2005)

Media art certainly does not fit easily within Klein’s description of ‘scripted space’. One could also be forgiven for thinking it is perceived as too clever, or too cheeky for its own good. The field is always experimenting, adapting, re-inventing and expanding with a multitude of social and cultural narratives alongside its use of technology. [5] (Blais & Ippolito 2006). The general view is that it’s just too complex and too fast for traditional art critics, galleries and institutions to catch up with. On some part, this is true – with its intrinsic connectedness, its ‘fluent’ networks – its multiple contexts – its critical, social and political dialogues – its adaptive behaviours when using code (an international language) – the ability to cross over into different practices, with verve. Yet, it is a contemporary art practice offering significant rewards when engaged with and explored further. Christiane Paul, in her essay “Challenges for a Ubiquitous Museum” writes, “Nethertheless, its integration is in museums’ own best interest: new media art constitutes a contemporary artistic practice that institutions cannot afford to ignore. It can also expand its notion of what art is and can be.” [6] (Paul 2008).

Arguably, it is the most ‘contemporary’ art practice. But, it still defies acceptance and dedicated integration from the mainstream art establishment. In September 2012, Claire Bishop wrote an article on Art Forum’s web site, asking “WHATEVER HAPPENED TO DIGITAL ART?” [7] Bishop argues, there are no signs of digital art being represented in the contemporary art world by artists themselves, and asks why so few contemporary artists engage with “the question of what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital, [and] reflect deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitization of our existence?” [ibid] Bishop says there seems to be a nostalgic nod by artists towards analogue technology “The continued prevalence of analog film reels and projected slides in the mainstream art world seems to say less about revolutionary aesthetics than it does about commercial viability.” [ibid]

Bishop’s article focuses on artists who do not engage with the questions she raises. By doing this Bishop introduces a telling blind spot; where there (really) should be a more in depth survey, analysis and discussion on the thriving discourse and practice of digital art and media art culture. Bishop bypasses, discussing the relevance of ‘media art’ as part of contemporary art culture, and relegates it into what she terms as a ‘specialist sphere’. Her distance from the ‘actuality’ of media art practice epitomizes a common failing where academics and critics, not directly engaged with the art they discuss, end up misrepresenting its deeper contexts and real values. This is noticeable when Bishop only includes commercially known artists, and not emerging media artists. An effective tactic in keeping others down whilst proclaiming there are ‘no others’, a highly effective mechanism exploited by the art elite. Whether Bishop is aware of this or not, the background story here is that thousands of artists and their livelihoods are threatened by ill-informed, perceptions. The result is that artistic emancipation is given a wide birth, or seen as a threat whilst authorized, and marketable art brands are given greater resonance and representation above others. The art elite, and its hierarchies dependent on their brands, stand strong against (other) art and is treated as a threat to their own, economic based franchises.

This is not to say those not included in Bishop’s article are not seen by many others – thankfully, they are. If we move our (distracted) gaze away from (mainstream) art establishment eyes, a less restrictive vision begins to unfold. Artists, audiences, writers and curators engaged with media art culture are thriving and are gaining recognition and impetus, in spite of top-down, processes of commercialized, methods of filtering and institutionalized denial. Media art practice carries on regardless with its social and cultural diversity and its naturally transdisciplinary initiatives. Exploring beyond a ‘scripted’ art world and its reductive ‘marketed’ mythologies. The audience has played a significant role in bringing about this change. Everyday people are choosing to find their own examples of what they consider to be art, rather than just reading approved promotions by the mainstream art press. There are countless examples of contemporary, media art works being seen in galleries, on the Internet and different types of spaces, by artists such as, Annie Abrahams, Julian Oliver, Thomson and Craighead, Mary Flanagan, Genetic Moo, Kate Rich, Dominic Smith, Sarah Waterson, and Heath Bunting (the list goes on). All these artists are experiencing recognition as ‘contemporary artists’ in the ‘wider’ art world and extended, cultural communities.

“Museum curators are sometimes surprised to discover that more people surf prominent Internet art sites than attend their own brick-and-mortar museums.” [8] (Jon Ippolito)

The strange contradiction of being told that something is different to what one actually knows through ‘grounded’ experience creates a situation of distrust. This awkward state of affairs brings to notice that other forces are at play. Pre-post-modern questions relating to ‘authenticity’ come to the fore; as well as critical enquiries asking, on whose ‘authority’ such decisions are made? Naturally, realisations escalate with concerns that art is rarely considered on its merits, and it is more about conforming to strategies in-line with top-down, market led appropriation, this is – what creates the divide. We are then left with an art culture where artists are merely consumer brands, representatives and ambassadors of conventional taste, no matter how radical the contemporary art world or academic wisdom tries to pretend it is. “The more art meets the demands of business, governments and the super-rich, the more the promise of that freedom falters.” [9] (Stallabrass 2011)

This refusal of allowing other art for a more marketable set of franchises moves into totalitarian forms of enterprise, where production of culture is issued through mechanisms of marketing defaults rather than intuitive investigation and wider societal inclusion. We are presented with a spurious version of art-reality, a false consciousness dedicated to the embodiment of a class where a filtering out of difference creates a homogeneity in which we are forced to see art much like merchandise in a shopping mall. Celebrity, genius and scarcity become the main selling points in established art venues and traditional art magazines. In America, individuals such as Cory Archangel are presented above others whilst those who openly critique culture in their art work are less recognised. Some may feel that it is a positive step that Archangel is currently successful in these institutional frameworks. That, if particular individuals are selected as worthy of mainstream acceptance and support it will have a ‘Trickle Down’ effect, where other artists will also be included and experience similar accolades in time, and “If the rich do well, benefits will “trickle down” to the rest.” [10] (Blair)

But, what if these artists prefer by choice to be part of an art world less based on hegemony; and are more interested in being closely connected with their grass root art cultures, and are less interested in art celebrity culture? What if the art itself consists in its make-up similar values to those musicians in the Indie Music scene? What if this art is asking important questions that deserve a dialogue which goes deeper than marketable products, and proposed celebrity genius? Gregory Sholette explores this subject further in his book “Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture” [11], proposing that art thrives in the independent and non-commercial sectors and the material produced by unrepresented artists, feeds the mainstream to sustain a few artists within the art world elite. He sees those ‘left out’ of the branding exercises prescribed by the corporate run, contemporary art world, as ‘Dark Matter’. Sholette borrows the term “Dark Matter” from the science of cosmology, which refers to the immense quantity of non-reflective material that we cannot see out there, in the universe. In theory, this invisible matter makes up most of the universe, and is estimated to constitute 84% of the universe and 23% of it is mass energy. [12] (Hinshaw 2010) “Like its astronomical cousin, artistic Dark Matter makes up most of the cultural universe in contemporary, post-industrial society. Yet, while cosmic Dark Matter is actively being sought by scientists, the size and composition of artistic Dark Matter is of little interest to the men, women and institutions of the art world.” [13] (Sholette 2011)

Media Art, can be considered to be a part of this Dark Matter. Yet, there are examples where artists using technology have found ways to survive using their technical skills, by becoming innovative. This ambigious territory of artists moving into the creative industry field, where artists act as entrepreneurs, is complex and based on survival. Because the mainstream art world has not given these artists the overall recognition in an uncertain world from suffering recession, unless your lucky enough to be some of the few receiving an inherited income, survival is the main issue. The powers of neoliberalism continue to advocate a program of mass privatisation, deregulation, and marketisation, and the breaking down of educational funding world wide, producing mass global and local poverty. “Meanwhile, the same system imprisons everyone’s creativity in the prism of brutal economic “necessity.“ Today’s Van Goghs are working at McDonalds. Tomorrow’s Mary Shelleys are graduating owing a fortune in student loans.” [14] (Haiven 2012)

There is a demand for artists to introduce themselves as ‘New’, and ‘exciting’, as technicians feeding the creative economy, as in what Haiven terms as ‘creative capitalism’. In part, it creates extra confusion for media art culture, which has helped in the establishing a schizm, the term ‘New Media Art’. And yes, technology combines all of these different digital art processes and its ever widening, interrelated disciplines. Yet, when using a simple word such as ‘New’, it proposes as part of its meaning that it’s all about the ‘New’, as in, use of ‘New technology’ as an outright goal or a means to an end. This is a misleading term, and does not acurately reflect a field of practice incorporating crossovers and transdisciplinary understandings, uniting our engagement and experimentation with technology at a ‘variety of levels’, which also include ecological tendencies as well as social interpretations. Out of this, arrives a filtering process whereby assumptions and prescribed definitions reflect upon those who pragmatically abide with the dominating rules, or just so happen to fit into this reductionist gauge. In one sense, this relates to a form of top-down ‘cultural’ curating and then moves into other modes of standardization, initializing ‘extra-loaded’ mono-cultural themes prompting domination. This instigates conditions where on the whole artists working with technology become valued not because of their content or ideas, but mainly by the technological innovation itself.

And yes, innovation and invention is an imaginative means to explore, proceed and develop as a race. But, innovation as technology is ‘one’ factor, a segment which all too often distracts us from a bigger story. Emphasis on the ‘New’ bound up with ‘innovation’ falls into a paradox where technological determinism, ‘is’ the course of reason, fitting closely alongside an invasive, market driven ideology. The values then become purely measured by economics as a finite, a singular function that belies the intricacies of the ecologies needing attention within the art’s wider multi-relational contexts. Andrew Feenberg in his paper “Ten paradoxes of Technology” writes “Under capitalism control of technology is no longer in the hands of craftsmen but is transferred to the owners of enterprise and their agents. Capitalist enterprise is unusual among social institutions in having a very narrow goal—profit—and the freedom to pursue that goal without regard for consequences.” [15] (Feenberg 2010)

The Media Art field’s use of open networks has introduced an autonomy that has brought about a deeper understanding of the medium, and how to exploit it creatively. Appropriation of the software and the hardware has shaped how artists interact with each other. Peer critique and shared ownership of ideas have enabled small groups and communities to learn and initiate projects together. These networks have worked as doorways to connect people with other cultures, outside of their own nation states, museums, institutions and government focused ideologies. A constant dialogue and the swapping of knowledge, files and projects, peer collaboration, all nurtured by curiosity, generosity and shared interests. This has loosened the hard-edged, fabric of centralization.

A willingness to transform our ideas and intentions not soley based on ‘proprietorial’ dependencies, and a fetish for the ‘New’, allows space for ‘different versions of the new’ and ‘old’ dialogues to evolve. This enables the embracing of holistic gradations and interactions with others, which also include differences; possibilities and diversities connecting with ecology and a variant of creative expressions. James Wallbank in his essay for ISEA in 2010 wrote “Creativity transforms value. Defining a four-year-old computer as “obsolete” does not speak to the utility of the object (it’s still a powerful production and communications platform) but indicates its user’s unwillingness or inability to continue to be creative with it.” [16] (Wallbank 2010) Taking control of the media we use does not mean being buying the latest gadget, it means that we are aware of our responsibility to be more informed about the technology we use.

In his article “Open Source Art Again“, Rob Myers writes “Software is used to achieve many different ends within pluralistic society. Its use is as widespread and diverse as the written word was following the invention of the printing press. Free Software can therefore be understood historically and ethically as the defence of pluralistic freedom against a genuine threat. It is an ethical issue, a matter of freedom. This is very different from being a new method of organization or a more efficient means of production.“ [17] (Myers 2006) Control over one’s tools of creative production is now, as significant as having control over one’s creative ideas. And, media art as an art practice, has gained various attributes which allow processes of self-autonomy. There is something about working with technology and the Internet that changes our perception of the world, and how we operate in it. The world becomes less definable as nations and states. It evolves into a way of engaging and understanding other things, other worlds, other possibilities; touching on aspects of being able to re-edit ‘source’ materials, whether it be hardware, software or code, and bringing this knowledge with its learned experiences into, real-life situations.

DIWO History and its Context.

Within media art culture, DIWO has cultural and historical links with Net Art and Tactical Media. DIWO includes other influences, such as Fluxus and Situationism. It owes much of its awkwardness and anti-establishment values to one particular movement in music culture, which is punk, drawing upon its D.I.Y attitude as inspiration. DIWO is playful re-interpretation and fruition of some of the principles, and reasons why Furtherfield was originally founded, back in 96-97. We experienced first-hand, as artists in the 80s and well into the 90s, a UK art culture mainly dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi. Even now, British art culture is dominated by and large, a commercially orientated, uncritical and non-reflective hegemony. Inequalities and gate-keeping are a standard behaviour, justified by spurious and romantic notions of genius, within tightly controlled, mono-cultural frameworks.

“Furtherfield’s roots extend back through the resurgence of the national art market in the 1980s, to the angry reactions against Thatcher and Major’s Britain, to the incandescence of France in May 1968, and back again to earlier intercontinental dialogues connecting artists, musicians, writers, and audiences co-creating “intermedial” experiences.” [18] (da Rimini 2010)

When examining these hierarchies we notice the social divisions are a throw back from a very traditional period of British culture; bound in a colonial history of nationalism and imperialism. Of course, such historical traits are not bound only within the borders of the United Kingdom. It took an insightful American, John Dewey, who in spring 1932 gave a series of lectures at Harvard University, on the Philosophy of Art, to open up this issue. Out of these lectures grew his 1934 publication Art as Experience. He says “It erects these buildings and collects their contents as it now builds a cathedral. These things reflect and establish superior cultural status, while their segregation from the common life reflects the fact that they are not part of a native and spontaneous culture.” [19] (Dewey 1934)

“From adolescence I had visited the Tate, read the Art books and generally pulled a forelock in the direction of the cult of genius, on cue relegating my own creativity to the Victorian image of the rabid dog. We know well enough that this was how it was supposed to be. The historical literature on ‘rational recreations’ states that, in reforming opinion, museums were envisaged as a means of exposing the working classes to the improving mental influence of middle class culture. I was being innoculated for the cultural health of the nation.” [20] (Harwood 2012)

In 2001, Graham Harwood [21] received the first online commission from Tate Gallery London for the art work “Uncomfortable Proximity”. “This work forced me into an uncomfortable proximity with the economic and social elite’s use of aesthetics in their ascendancy to power and what this means in my own work on the internet.” [22] (Harwood 2006) The first section of work maps high society rituals of tastefulness and its inherent hypocrisy. The second, representations and histories of different people such as friends, family and others, who are unseen in terms of the institution’s remit of tastefulness. To do this he used the historically respected paintings (on-line images) on the Tate web site by artists such as Turner, Hogarth, Hamilton, Gainsborough, Constable and others.

Graham Harwood. Hogarth, My Mum 1700-2000.

Viewing the visual images/collages created by Harwood, reminds one of the moment when Lord Henry, in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray'[23] views his constantly changing, disfigured self portrait. The facade of greatness is revealed to be less attractive, less honourable and deeply disturbing. Harwood’s approach in offering the viewer to click on the image to see what lies them behind shows the people he represents, to be seen as lurking secrets, as ghosts, mutants, lepers and outsiders. “Tate Britain stands on the site of Millbank penitentiary incorporating part of the prison within its own structure. The bodies of many of the inmates remain concreted into the foundations of the building. The drains that run from the building to the Thames, a stones through away, bleed this decay into the silt of the Thames.” [24] (Harwood 2006)

Dewey’s writings and Harwood’s art work “Uncomfortable Proximity”, explore how we are still governed by the same elite structures, informing (or appropriating) our perceptions and engagement in art culture today. DIWO’s intentions reflect Furtherfield’s own critical and practicle approach, in challenging aspects of art culture where false credence is given to a few individuals over many others, which is usually based either on personality alongside depoliticized artworks. Recently, in an article by John A. Walker on the artdesigncafé web site, discussed how art culture is still haunted by the power of Charles Saatchi.

“Arguably, as an art collector Charles Saatchi has become a brand in his own right—when he buys art works they and the artists who created them are immediately branded.“ [25] (Walker 2010)

The Charles Saatchi branding iron is a limited edition work of art conceived by John A Walker.

BritArt’s dominance of the late 80s and 90s UK art culture dis-empowered the majority of British artists, dominating other artistic discourse and fuelling a competitive and divisive attitude for a shrinking public platform for the representation of their own highly marketed work. This resulted in many artists replicating this art in order to be accepted into mainstream galleries and art magazines. This tactic of domination through market forces and elite friends in high places created what we know as BritArt. Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art.

“The cult of the personality is, of course, a central element in all totalitarian art. While both fascism and democracy are variants on the capitalist mode of economic organisation, the former adopts the political orator as its exalted embodiment of the ‘great man,’ while the latter opts for the artist. This distinction is crucial if one is to understand how the yBa is situated within the evolving discourse of totalitarian art.“ [26] (Home 1996)

Whoever controls our art – controls our connection, relationship and imaginative experience and our discourse around it. The frameworks and conditions where art is accessed, seen and discussed are significantly linked to representation and ownership. Socially and culturally, this process of abiding by specific rules and protocols, defines who and what is worth consideration and acceptance. For art to be accepted within these ‘traditional’ frameworks a dialogue reflecting its status around a particular type of function kicks into place, it must adhere to certain requirements. Whether it is technological or using traditional skills (which may not necessarily be digital) the art or artist must in some way conform to specific protocols before it can be allowed into the outer regions of officially condoned culture. This process adds merit to the creative venture itself and feeds a systemic demand based around innovation in a competitive marketplace. This closes down possibilities for a wider, creative dialogue. When we experiment beyond the limits of assumed notions of ‘excellence’ or ‘genius’, and challenge the mechanisms and mannerisms of mainstream culture and its dominant values something else emerges and evolves, an imaginative exploration of engagement opens up new forms of art, but also new, shared, connected and potentially critically informed values.

The term DIWO OR D.I.W.O, “Do It With Others“ was created in 2006 [27] (Garrett 2006), on Furtherfield’s collaborative project ‘Rosalind’. [28] An upstart new media art lexicon that Furtherfield built with others, born in 2004.

“(or Diwo’s, or Diwo groups) Expanded from the original term known as D.I.Y. (Do It Yourself). D.I.W.O ‘Do It With Others’. Is more representative of contemporary, collaborative – art practice which explores through the creative process of using networks, in a collective manner.” (Garrett ibid)

DIWO (Do It With Others) is inspired by DIY culture and cultural (or social) hacking. Extending the DIY ethos with a fluid mix of early net art, Fluxus antics, Situationism and tactical media manoeuvres (motivated by curiosity, activism and precision) towards a more collaborative approach. Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art.

The Mail Art Connection & DIWO’s Infrastructural Tendencies.

“It is in the use of the postal system, of artists’ stamps and of the rubber stamp that Nouveaux Realisme made the first gestures toward correspondence art and toward mail art.“ [29] (Friedman 1995)

Mail Art is a useful way to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on your own terms. With DIWO projects we’ve used both email and snail mail. Later, we will return to the subject of email art and how it has been used for collective distribution and collaborative art activities; but also, how it can act as a collaborative, remixing function or tool, and be an art piece in its own right, on-line and in physical environments.

“[…] many Fluxus works were designed specifically for use in the post and so the true birth of correspondence art can arguably be attributed to Fluxus artists.” [30] (Blah Mail Art Library)

Many consider George Maciunas was to Fluxus, what Guy Debord was to Situationism. Maciunas set up the first Fluxus Festival in Weisbaden in Germany, 1962. In 1963, he wrote the Fluxus Manifesto in 1963 as a fight against traditional and Establishment art movements. In a conversation with Yoko Ono in 1961, they discussed the term and meaning of Fluxus. Showing Ono the word from a large dictionary he pointed to ‘flushing’.

““Like toilet flushing!“ he said laughing, thinking it was a good name for the movement. “This is the name“, he said. I just shrugged my shoulders in my mind.” [31] (Ono 2008)

“The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.“ [32] (Parmesani 1977)

Maciunas’s ambitions were strongly based on an art that was free for all by replacing it with Fluxus; a creativity which could be realised anywhere and anyhow. Art with autonomy was the whole point of Fluxus, to “promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art”. [33] (Corris 2009) Maciunas’s refusal to have any Fluxus works signed was a critique on the concept of genius, scarcity and ownership. This made things difficult for dealers and collectors to brand the works in accordance to ‘genius’ and ‘personality’ for economic value; they were gifts, acts of imaginative generosity. These acts of generosity were part of a broader critique of capitalism during the 60s and 70s, they were gifts of resistance.

DIWO is a gift of resistance in the 21st Century, exploring relational and hybrical realizations. It is socially informed, constantly adapting, intuitive and grounded. It can collide with mainstream culture but also exist deeper in the networked shadows, in accordance to the needs of who ever participates at any given time. It is creativity with a radical adge, asking questions through peer engagement, as it loosens up infrastructural ties and frameworks. It is a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age. By drawing on past experiences with pirate radio, historical inspirations from Punk, with its productive move towards independent and grass roots music culture, as well as learning from Fluxus and the Situationists, and peer 2 peer methodologies; we transform ourselves into being closer to a more inclusive commons. We transform our relationship with art and with others into a situation of shared legacy and possible moments of active emancipation.

“[…] art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns“ [34] (Bauwens 2010)

The infrastructural tendencies that occur when ‘the many’ practice DIWO; informs us we are in a constant process which redefines the role of the individual, and our notions of centralized power and behaviour. This process also reevaluates concepts of art as scarcity. It moves us away from an attachment with socially engineered dependencies, usually centred around consumer led desire, by changing the defaults. If we change the defaults we change the rules, opening up possibilities for more agency involving relational contexts.

“The network is designed to withstand almost any degree of destruction to individual components without loss of end-to-end communications. Since each computer could be connected to one or more other computers, Baran assumed that any link of the network could fail at any time, and the network therefore had no central control or administration (see the lower scheme).” [35] (Dalakov 2011)

Even though the Web and DIWO possess different qualities they are both essentially, forms of networked commons. They both belong to the same digital complexity, each are open systems for human and technological engagement. DIWO rests naturally within these frameworks much like other digital art works or platforms but have key differences. If we consider the structures of Facebook, Google, MySpace, iTunes and now Delicious, they are all centralized meta-platforms, appropriating as much users as possible to repeatedly return to the same place. In contrast to the original function and freedom of the Internet and its seemingly infinite networked nature, these meta-platforms are closed systems. Not, necessarily closed as in meaning ‘you cannot come in’, but closed to others in respect of core values, exploiting human interaction and their uploaded material, and openly ‘given’ data-information. These centralized meta-platforms close choices down through rules of ownership of personal data, as well as introducing more traditional standards of hierarchy.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron saw this curious dichotomy way back in 1995. Where on one hand we had the dynamic energy of sixties libertarian idealism and then on the other, a powerful hyper-capitalist drive, Barbrook and Cameron termed this contradiction as ‘The Californian Ideology’. “Across the world, the Californian Ideology has been embraced as an optimistic and emancipatory form of technological determinism. Yet, this utopian fantasy of the West Coast depends upon its blindness towards – and dependence on – the social and racial polarisation of the society from which it was born. Despite its radical rhetoric, the Californian Ideology is ultimately pessimistic about real social change.“ [36] (Barbrook and Cameron 1995)

With these contexts in mind DIWO, is not an absolute ‘technological determined’ factor, but a thing of many things, a social activism with a commons spirit going as far back as The Diggers.

“The Diggers [or ‘True Levellers’] were led by William Everard who had served in the New Model Army. As the name implies, the diggers aimed to use the earth to reclaim the freedom that they felt had been lost partly through the Norman Conquest; by seizing the land and owning it ‘in common’ they would challenge what they considered to be the slavery of property. They were opposed to the use of force and believed that they could create a classless society simply through seizing land and holding it in the ‘common good’.” [37] (Fox)

Three elements pull DIWO together as a functioning whole, and it can mutate according to a theme, situation or project. These three contemporary forms of (potential) commons mainly include; the ecological – the social – and the networks we use. By appropriating these three ‘possible’ processes of being with others; combined, they introduce and enhance potential for an autonomous and artistic process to thrive, further than the limitations of any single or centralized point of presence. It brings about small societal change; as long as we are conscious of the social nuances for a genuine and critically engaged mutual collaboration.

“Collective doings are motors of change transforming how people create (art, software, learning situations, community gardens, journalism) until the point that solitary production seems anachronistic and somewhat joyless. These motors can drive more radical change, as people collectively place their bodies into contested zones (reclaiming the streets, university occupations, climate camps) forcing struggles into public awareness.” [38] (da Rimini 2010)

DIWO works by the same principles functionally as a p2p infrastructure, and requires the following “set of political, practical, social, ethical and cultural qualities: distribution of governance and access to the productive tools that comprise the ‘fixed’ capital of the age (e.g.: computing devices); information and communication systems which allow for autonomous communication in many media (text, image, sound) between cooperating agents; software for autonomous global cooperation (wikis, blogs etc); legal infrastructure that enables the creation and protection of use value and, crucially to Bauwens’s p2p alternatives project, protects it from private appropriation; and, finally, the mass diffusion of human intellect through interaction with different ways of feeling, being, knowing and exposure to different value constellations.” [39] (Garrett and Catlow 2012)

“Online creation communities could be seen as a sign of reinforcement of the role of civil society and make the space of the public debate more participative. In this regard, the Internet has been seen as a medium capable of fostering new public spheres since it disseminates alternative information and creates alternative (semi) public spaces for discussion.“ [40] (Morell 2009)

Ecological media artworks turn our attention as creators, viewers and participants to connectedness and free interplay between (human and non-human) entities and conditions. The foundations of the Do It With Others art context, that privileges FLOSS skills sharing and commons-based peer produced artworks and media over the monitored and centrally owned and controlled interfaces of corporate owned social media. This is the spirit of DIWO, if it’s centralized and controlled by a corporate entity, it ain’t DIWO.

Suggested Action:

Art organizations, museums and art magazines should promote contemporary media art culture. Inivite emerging artists, art groups to talk about their work. Invite media arts practioners, theorists, organizations and communities to share their skills, knowledge and expertise. This includes national arts institutions, regional arts venues, mainstream art magazines and critical art magazines.

Barrier: Mainstream art world culture is currently biased towards the values of the powerful, whether it is institutional power or economic power. It’s evidenced through the tight networks of media, international art markets and corporate sponsorship, and national insitutions. These act as constraints on the resources, ideas, platforms, ethics, aesthetics and technological engagements of a wider and contemporary culture, and also restricts ‘possible’ connections and exchanges between artists and audiences.

Target (stakeholders): Art organizations, Museums, Galleries, Funding groups, Sponsers, Applied Research Funders, Universities.

Solution: Go and see the work created by contemporary media artists and look at the different sets of values found in their works, tools and processes and allow their artworks to define current trends, ideas and values, and contemporary art contexts. Look at web sites and on-line portals where these art communities are sharing dialogue around their works and the theories being discussed. Visit sites where critics and artists write on the subject of media art and related practices.

Extra Suggested Actions:

1. Art organizations, museums and art magazines, and art institutions should engage in open investigations into grass root initiatives by D.I.Y, DIWO (Do It With Others), and Peer 2 Peer groups. Study their works, support and promote them as part of their artistic programs. They should also invest in the development of these projects (commissions, residencies, conferences, exhibitions and work shops etc). This will decentralize art culture and meet diverse audiences and communties on their own ground. It will also help them to learn about and appreciate the values and benefits of this important work being produced.

2. Make available for distribution at gallery bookshops and art and esign colleges, works currently being explored and written by theorists and artists writing about Media Art, this includes software art, art and hacktivism, psychogeography, net art, networked art, game art, glitch art, grassroots artistic innovation, interdisciplinary practices and contemporary forms of art dealing with technology, ecology, and free and open source technology.

3. Government funding agencies, development agencies and policy makers, local and national cultural policy makers, should give their support to ideas around alternative and mixed economies. And connect with artists and arts groups who are working with D.I.Y, DIWO (Do It With Others), and Peer 2 Peer projects. These are dedicated and informed groups creating new forms of shared commons as innovation, concerning climate change and the current economic crisis. Many of these groups are successfully exploiting the technological resources of alternative hardware and software, as part of a growing free and open source movement. Code and art are both international languages, where much of the most exciting and imaginative projects are being explored collaboratively. Jobs, funding and research into these areas will provide a more sustainable culture where groups involved in these practices can produce accessable and inclusive resources for artists, designers, ecologists, students and the public. They can also provide data and case studies for academic research.

References :

[1] Can Art do Technology and Social Change? Ruth Catlow. October 2010.

http://www.axisweb.org/dlForum.aspx?ESSAYID=18115

[2] Wendy Fonarow, PhD, is a Los Angeles based Anthropologist specializing in live music, ritual, and performance. Her expertise is in the area of the culture of indie music and American holidays. She is an Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Glendale College. http://www.indiegoddess.com/

[3] Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture). Dr. Wendy Fonarow. Wesleyan; annotated edition edition (July 10, 2006) P66-67.

[4] Norman Klein. “Inside the Stomach of the Dragon: The Victory of the Entertainment Economy”. In Eyebeam Journal: Dissecting Art and Technology (January 2005). http://www.eyebeam.org/reblog/journal/archives/2005/01/inside_the_stomach_of_the_dragon.html (web page now missing).

[5] At the Edge of Art. Joline Blais , Jon Ippolito. Thames & Hudson (Mar 2006).

[6] Christiane Paul. Challenges For a Ubiquitous Museum: From White Cube to The Black Box and Beyond. New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Christiane Paul (Editor). (2008) P. 74.

[7] DIGITAL DIVIDE: Claire Bishop On Contemporay Art And New Media.

http://artforum.com/inprint/issue=201207&id=31944

[8] Jon Ippolito. Ten Myths of Internet Art.

http://www.nydigitalsalon.org/10/essay.php?essay=6

[9] Julian Stallabrass. Contemporary Art’s Pyrrhic Triumph. ‘The Hollow Triumph of Contemporary Art’, The Art Newspaper Magazine, June 2011, pp. 7-8.

[10] Trickle-down Economics and Ronald Reagan. Jim Blair (last visited 25/9/12) http://www.bigissueground.com/politics/blair-trickledownreagan.shtml

[11] Gregory Sholette. Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. Pluto Press (January 4, 2011)

[12] Hinshaw, G. F. (29 January 2010). “What is the universe made of?“. Universe 101. NASA/GSFC. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

[13] Gregory Sholette. Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. Pluto Press (January 4, 2011)

[14] Privatizing creativity: the ruse of creative capitalism. Max Haiven on October 10, 2012.

http://artthreat.net/2012/10/privatizing-creativity/

[15] Andrew Feenberg. “Ten Paradoxes of Technology,“ Technē, vol. 14, no. 1, 2010. (Last viewed 01/09/2012) http://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/paradoxes.pdf

[16] Life on the Trailing Edge: Ten Years Exploring Trash Technology. James Wallbank. (2010). (Last visited Aug 2012) http://www.isea2010ruhr.org/de/conference/tuesday-24-august-2010-dortmund/p17-media-politics-of-the-local#Wallbank

[17] Open Source Art. Rob Myers. September 2006. https://github.com/robmyers/open_source_art

[18] Francesca da Rimini. Socialised Technologies, Cultural Activism, and the Production of Agency. Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities and Social Sciences 2010. P 194.

[19] Art as Experience John Dewey. Perigee Books (24 Sep 2009) P.336

[20] Graham Harwood. http://www.gold.ac.uk/cultural-studies/staff/g-harwood/

[21] http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/mongrel/collections/default.htm

[22] Tate BricABrac. Graham Harwood. http://mongrel.org.uk/node/14

[23] The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Picture of Dorian Gray, by Oscar Wilde.

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/174/pg174.txt

[24] Museums and Prisons. Graham Harwood. http://mongrel.org.uk/node/9

[25] Charles Saatchi branding iron : Order now! “You are nobody in contemporary art until you have been branded.” John A. Walker. September 2010 http://www.artdesigncafe.com/Charles-Saatchi-brand-iron-Walker

[26] THE ART OF CHAUVINISM IN BRITAIN AND FRANCE by Stewart Home. Published in everything # 19, London May 1996. (Last checked 30th Oct 2011). http://www.stewarthomesociety.org/2art.html

[27] DIWO term on Rosalind By Marc Garrett – 08/11/2006

http://www.furtherfield.org/lexicon/diwo

[28] Rosalind, an upstart new media art lexicon, born in 2004.

http://www.furtherfield.org/get-involved/lexicon

[29] Friedman, Ken. 1995. “The Early Days of Mail Art: An Historical Overview.” In Eternal Network. A Mail Art Anthology. Chuck Welch, editor. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press. Pp. 3-16.

[29] Artist of the week 26: George Maciunas. Jessica Lack. Last visited 20th Aug 2012.

[30] BLAH LIBRARY: IDENTITY IN THE ETERNAL NETWORK.

http://reocities.com/soho/5921/identity.html

[31] SUMMER OF 1961 by Yoko Ono. April 2008.

[32] Loredana Parmesani, text under the entry “Poesia visiva”, in “L’arte del secolo – Movimenti, teorie, scuole e tendenze 1900-2000”, Giò Marconi – Skira, Milan 1997

[33] Michael Corris. Fluxus. From Grove Art Online © 2009 Oxford University Press.

http://www.moma.org/collection/theme.php?theme_id=10457

[34] An interview with Michel Bauwens founder of Foundation for P2P Alternatives. Furtherfield. By Lawrence Bird 2010.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/interview-michel-bauwens-founder-foundation-p2p-alternatives

[35] Georgi Dalakov. “Paul Baran”. History of Computers web site. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

http://history-computer.com/Internet/Birth/Baran.html

[36] THE CALIFORNIAN IDEOLOGY. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron (August 1995).

http://www.alamut.com/subj/ideologies/pessimism/califIdeo_I.html

[37] 1642-1652: The Diggers and the Levellers. A history of the radical movements the Diggers and the Levellers which sprung up around the English Civil War. Jim Fox

From Revolutions Per Minute. http://libcom.org/history/articles/diggers-levellers-1642-52/

[38] Francesca da Rimini. Socialised Technologies, Cultural Activism, and the Production of Agency. Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities and Social Sciences 2010. P 200.

[39] Remediating the Social. DIWO: Doing It With Others. Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow. P 69. Published by Electronic Literature as a Model for Creativity and Innovation in Practice. University of Bergen, Department of Linguistic, Literary and Aesthetic Studies PO Box 7805, 5020 Bergen, Norway. Editor: Simon Biggs. University of Edinburgh. 2012.

[40] “Online creation communities for the building of digital commons: Participation as an eco-system?” Contribution to the panel on “Organizational principles and political implications” of the International forum on free culture – Barcelona October 30 2009. Online creation communities for the building of digital commons: Participation as an eco-system? Fuster Morell, Mayo (2009) Pdf. P12. http://www.onlinecreation.info/?page_id=27

Is DYI DIWO the solution to art science collaboration ?

[…] https://seadnetwork.wordpress.com/white-paper-abstracts/final-white-papers/diwo-do-it-with-others-art…/ […]

Baffinland commemorative

Humanely underway, welcoming oxygenated sustenance for overdue and quested neighborhood collabs: Mesh net, Nano backbone, with citizen-scientist, and open-nerves continuing to be connected.

toward global …”Artistic co-creation…”

1980 New Music America

http://www.d.umn.edu/~lbrush/lbarchivesg.html#anchor268788

http://www.turbulence.org/blog/archives/cat_opportunities_events_resources.html

This is the better link for The Californian Ideology: http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/17/the-californian-ideology-2/

[…] Qu’est-ce que DIWO? Marc Garrett dévoile les secrets de la “co-création artistique décentralisée dans cet article. […]

Hi, after reading this awesome post i am too glad to share my know-how here with colleagues.

[…] Garrett, M (2014) “DIWO: Artistic Co-creation as a Decentralized Method of Peer Empowerment in Today’s Multitude,” Sead White Papers […]